ITALIAN RHODES (Rodi italiana)

During the Italo-Turkish War started in 1911 the Kingdom of Italy occupied Rodi (called Rhodes in English) & the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean sea.

PALAZZO DEL GOVERNO (today the offices of the "Prefecture of the Dodecanese"), built by architect Di Fausto in 1927

With the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923 the Dodecanese was formally annexed by Italy, as the ''Possedimenti Italiani dell'Egeo''.

In the 1930s Mussolini embarked on a program of Italianization, hoping to make the island od Rhodes a modern transportation hub that would serve as a focal point for the spread of Italian culture in Greece and Levant.

The 1912 landing of Italian troops in Rhodes island

The main castle of the Knights of St. John was also rebuilt. The concrete-dominated Fascist architectural style integrated significantly with the islands' picturesque scenery (and also reminded the inhabitants of Italian rule), but has consequently been largely demolished or remodeled, apart from the famous example of the Leros town of Lakki, which remains a prime example of this architecture.

From 1923 to 1936 governor Mario Lago was able to integrate the Greek, Turkish and Ladino Jewish communities of the island of Rhodes with the Italian colonists, obtaining a so called "Golden Period" in the Italian Dodecanese with the economy and the society enjoying huge developments and harmony (http://www.dodecaneso.org/2336a.htm The "golden years" of governor Lago (in Italian).

From 1936 to 1940 Cesare Maria De Vecchi acted as governor of the Italian Aegean Islands promoting the official use of the Italian language and favoring a process of italianization, interrupted by the beginning of WWII (http://books.google.com/books?id=fJ3gVGqB1uQC&pg=PA436&lpg=PA436&dq=de+vecchi+dodecanese+italian+language&source=web&ots=gIgR81ZYv9&sig=2gIp1imYJUVYZH6iSY9gfq0KXck#PPA436,M1. De Vecchi even wanted to include the Italian Dodecanese (called also "Isole Egee italiane") in the project of Mussolini's Greater Italia.

In the 1936 Italian census of the Dodecanese islands, the total population was 129,135, of which 7,015 were Italians. Nearly 80% of the Italian colonists lived in the island of Rhodes, where there was an important Italian naval base. Aproximately 40,000 Italian soldiers and sailors were on military duty in the Dodecanese islands in 1940.

During World War II, Italy joined the Axis Powers, and used the Dodecanese as a naval staging area for its invasion of Crete in 1940. After the Armistice in September 1943, the islands briefly became a battleground between the Nazi Germans and the Italians. The Germans prevailed and although they were driven out of mainland Greece in 1944, the Dodecanese remained occupied until the end of the war in 1945, during which time nearly the entire Jewish population of 6,000 was deported and killed. Only 1200 of these Ladino speaking Jews survived, thanks to their lucky escape to the nearby coast of Turkey with some help from the Italian colonists of Rhodes.

There were 3 periods of the Italian presence in Rhodes: the first after the occupation in 1911 and until the treaty with the official annexation & Turkish renounce to the Dodecanese islands.; the second under Mario Lago rule and the third under the one of De Vecchi until the beginning of ww2.

Three years later (1943), after the fall of Mussolini and the capitulation of Badolio, the Germans would take over the islands ending formally the Italian presence & rule on the islands after more than thirty years.

Actually the citadel of Rhodes city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, thanks in great part to the large-scale restoration work done by the Italian authorities in what was "Rodi italiana" from 1912 to 1943.

The Rhodes government center showing the Italian flag in 1919

MARIO LAGO PERIOD (1923-1936)

During this period, there was a radical change in the nature of the Italian domination in the Dodecanese owing to the Italian de jure occupation and the ascend of Mussolini to power. We should also mention that the identification of this period with one person is nothing but coincidental. The governor had very broad legislative, administrative and judicatory jurisdiction.

A series of legislative regulations dealt a crushing blow to the traditional agricultural economy (still in the Middle Ages!) of the islands, such as the 1924 forestall law, which imposed numerous restraints on cultivation privileges and made appropriating land from the State easier. This deteriorated farmers’ position and often led to their proletarianization.

Save rebuilding the economy with the invasion of Italian businesses, Italian planning was mostly aimed at developing tourism. In 1933, 200,000 brochures and 30,000 tourist guides were printed in four languages. At the same time, 11 shipping companies connected the Dodecanese (mostly Rhodes) with the entire Mediterranean Sea.

Save rebuilding the economy with the invasion of Italian businesses, Italian planning was mostly aimed at developing tourism. In 1933, 200,000 brochures and 30,000 tourist guides were printed in four languages. At the same time, 11 shipping companies connected the Dodecanese (mostly Rhodes) with the entire Mediterranean Sea.

Rodi's famous "Grande Albergo delle Rose" in 1930

Though the numbers reported by several sources differ greatly from each other, there is no doubt that the migratory wave increased immensely during the Italian Rule. Migration was caused mainly by socio-economic factors, but it was encouraged by the favorable stance of the Italian authorities intending to establish Italian colonists in the place of emigrants. Their efforts had mixed results, since in 1936 Italians in the Dodecanese were no more than 16,711, most of whom had settled on Rhodes and Leros. Italians of Rhodes and Kos were farmers and had settled at new settlements organized as farming businesses. Those of Leros generally worked for the army and lived at the facilities of the city of Porto Lago at Lakki.

What marked the Italian Rule in the Dodecanese though was their activity in town planning. Besides, Lago himself would call this remarkable zoning, planning and building activity aimed at the colonization of places “stone policy

Their interference in town planning was not of the same extent on all islands. On Rhodes, Kos and Leros it was quite significant, defining up to now the character of these islands. On the rest of the islands, they only constructed middle-sized command posts and public service buildings dominating the ports. In May 1923, architect Florestano di Fausto was called from Rome in order to design anew the city of Rhodes. After the 1933 earthquake, the city of Kos was designed anew by Rodolfo Petracco. He also designed Porto Lago at Lakki of Leros, the only newly founded city. All of this interference in town planning was followed by the construction of imposing buildings and significantly improved the urban net. It was all based on extended practically inexpensive mandatory expropriations of building plots and residences.

DE VECCHI PERIOD (1936-1940)

De Vecchi didn’t make any new development plans; he just carried out those of his predecessor, whom he accused of being “ orientalist” among others. His loathing for what he thought was of “orientalist style” made him change the exterior of buildings. Their façades were covered with pietra finta lime-cast (Italian for “fake stone” ). It was a mixture of cement with sinter powder, similar in color and texture to the sinter of the buildings of the Knights’ era. Such examples are the Hotel of the Roses and the Court House, which were radically changed.

The few buildings constructed were characterized by the monumental fascist architecture aiming to inspire awe and respect among residents. This period ended when Italy entered the war.

Rodi's Teatro Puccini, when just built in 1937

Colonization policy was not limited in cities. A series of controversial decrees also changed the uses of land and its forms. Characteristic examples are the 1924 forestall law and the establishment of land register. The first one benefited impressively the environment but also damaged the agricultural economy. The latter organized and rationalized the uses of land but also became the medium for extensive changes of ownership.

Bank of Italy building (now Bank of Greece), created by Di Fausto

Bank of Italy building (now Bank of Greece), created by Di Fausto

DE VECCHI PERIOD (1936-1940)

As the fascist regime became harsher with the declaration of the empire (imperio), Lago was substituted for tetrarch fascist Cesare de Vecchi. He became governor and had both political and military power. De Vecchi’s main goal was radical italianization and institutional modernization of the islands. Therefore, he imposed radical changes in education with the new school regulation (July 21 1937), which practically established the total domination of the Italian language at schools (teaching Greek was only optional and with no books in the first classes of primary school).

Moreover, the system of administration, balancing between the traditional “ communal” system and the modernizing expectations of Italian fascism, altered significantly in 1937, when new mayors were appointed, the podesta, directly depended from the governor. The racist law for the preservation of the purity of the Italian race was also introduced in 1938. At the same time, a series of decrees imposed absolute equalization with the Italian law.

Rodi was linked to Italy by a regular air service since the mid 1930s. The "Aero Espresso Italiana" (AEI) had flight from Brindisi to Athens and Rodi with flying boats (AEI used mainly the "Savoia 55", but also the "Macchi 24bis"), as can be seen in the following propaganda poster:

Mixed courts of orthodox, muslim and Jews were abolished and their cases were heard in modern civil courts. Concluding contracts and issuing certificates came from religious communities under State services.

Moreover, the system of administration, balancing between the traditional “ communal” system and the modernizing expectations of Italian fascism, altered significantly in 1937, when new mayors were appointed, the podesta, directly depended from the governor. The racist law for the preservation of the purity of the Italian race was also introduced in 1938. At the same time, a series of decrees imposed absolute equalization with the Italian law.

Rodi was linked to Italy by a regular air service since the mid 1930s. The "Aero Espresso Italiana" (AEI) had flight from Brindisi to Athens and Rodi with flying boats (AEI used mainly the "Savoia 55", but also the "Macchi 24bis"), as can be seen in the following propaganda poster:

Mixed courts of orthodox, muslim and Jews were abolished and their cases were heard in modern civil courts. Concluding contracts and issuing certificates came from religious communities under State services.

The few buildings constructed were characterized by the monumental fascist architecture aiming to inspire awe and respect among residents. This period ended when Italy entered the war.

Rodi's Teatro Puccini, when just built in 1937

ITALIAN ARCHITECTURE IN RODI

Although the Italians landed on the island of Rodi in 1912 during their conflict with the Ottoman Empire, most of their architectural works on Rhodes were carried out during the era of Mussolini (who took power a decade later) and reflect the attitude of his fascist regime toward urban space. The past – the ancient past as much ass the Middle Ages & the Renaissance – became raw material for fascist rhetoric, as Dr. Medina Lasansky pointed out in her book “The Renaissance Perfected: Architecture, Spectacle & Tourism in Fascist Italy.”

In the 1920s and 30s many leading architects, archaeologists, historians and city planners of Rome collaborated to showcase ancient monuments and historic sites of the former Roman Empire in the light of the Duce’s vision of modern Italy as a metropolitan power center.

Public spaces, commercial facilities, churches, theaters, bridges, schools, sports facilities, villages and entire cities were either built or restored in Italy, as well as in the Italian territories in the Aegean and northern and eastern Africa. The central motif for this extensive building program was antiquity, both on a theoretical and practical level, and its apparent aim was the promotion of Fascism.

Family of an Italian "carabinieri" who was a farmer colonist in the outskirts of Rodi in 1941

Family of an Italian "carabinieri" who was a farmer colonist in the outskirts of Rodi in 1941

The aesthetics of this movement were not uniform, as the ruling Italians appointed to their ranks and glorified, on a case by case basis, ultra-modernists, rationalists, neo-historians and representatives of the "Novecento". However, the main thrust of everyone involved was the “cleansing” (or “liberation,” as they called it) of the past.

Thus, the restoration and/or reconstruction of the traces of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance included their redesign – their selective representation carried out according to a specific viewpoint, one that fit the regime and its values. Whether in Rome, Tuscany, Rhodes or Libya, the regime’s architects were summoned to create a “purified version" of the past that would extol the present.

The first civilian governor of the Italian Islands of the Aegean, and the one who left the most lasting impression on Rhodes, was the diplomat Mario Lago (1924-1936), who led his country’s efforts to impose Italian culture and to alter the ethnic make-up of the local population, while simultaneously attempting to banish the Greek language, culture and Orthodox religion.

Lago erected many public buildings; undertook numerous beautification projects in Rhodes’ historical center; restored medieval monuments; founded rural settlements; and adopted economic reforms – including measures to promote tourism. He was a pioneer in his time. Perhaps his most important legacy is the master plan he instituted for the city of Rhodes, which was comparable to those adopted in all the major cities of the West.

During Lago’s tenure, the monuments of the "Citta' vecchia" (in English "Old Town") were identified and protected; all the land in the immediate area around the city walls was declared a “zona monumentale” (monument zone) and construction came under tight controls. Large areas (e.g., the Ottoman cemeteries) were forcibly seized for reasons of public interest, while the new town established outside the walls followed the popular Italian model of the garden city, endowed with a modern infrastructure, including roads, water and sewer systems, street lighting and administrative and military buildings.

Photo of the first Stadium in the Dodecanese islands: the "Arena del Sole", created in 1932 just outside the old walls in Rodi city.

Most of the projects completed during this period bear the stamp of Fiorestano di Fausto (1890-1965), the most important architect of fascist Italy. In the space of three years (1923-1926), and before he suffered a rift with Governor Lago, Di Fausto had designed or redesigned an astonishing fifty buildings in the Dodecanese – houses, public buildings, churches, markets, schools, barracks – of which thirty-two had been completed or were under construction in 1927.

Most of the projects completed during this period bear the stamp of Fiorestano di Fausto (1890-1965), the most important architect of fascist Italy. In the space of three years (1923-1926), and before he suffered a rift with Governor Lago, Di Fausto had designed or redesigned an astonishing fifty buildings in the Dodecanese – houses, public buildings, churches, markets, schools, barracks – of which thirty-two had been completed or were under construction in 1927.

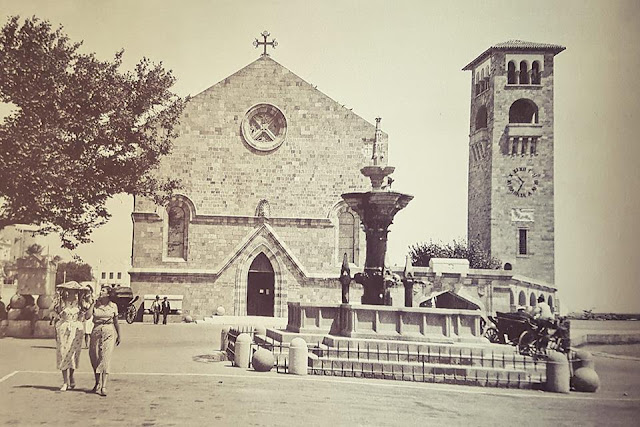

Among the achievements that can still be admired today are the Foro Italico, the city’s new administrative center atMandraki and the Italian (formerly Ottoman) Club, a lounge for Italian officers and senior civil servants. The Courthouse was restored in a style clearly influenced by Renaissance architecture. The Roman Catholic Cathedral of Saint John (known today as the Metropolitan Church of the Annunciation), with its characteristic bell tower and its famed sarcophagi of the Great Magistrates, was built in the New Town as a replica of an older, Hospitallers-era church destroyed in 1856.

Other buildings include the Maritime Administration and the "Grand Hotel of the Roses", with its distinctive dome, which continues to operate as a hotel and which constitutes one of the major landmarks of touristic Rhodes. Equally important was the Italians’ conservation work in the Old Town, especially their intervention at the "Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes", which they restored and turned into a museum (it remains one today).

Notable, too, are the archaeological surveys, excavations and restoration works carried out by the Italians at several sites in Rhodes, mainly at Ialysos and Lindos, and elsewhere in the Dodecanese Islands.

Lago was succeeded by Cesare Maria De Vecchi (1936-1940), one of the Quadrumvirs in Mussolini’s central ruling tetrarchy. He imposed harsh rules of government, particularly as the Second World War and the Greco-Italian War approached.

Wanting to further emphasize the “glory” of the Knights and their presence in Rhodes, and by association to extend that glory to the regime of which he was a founding member, De Vecchi had public buildings and new constructions cladded with "pietra finta" (faux stone),as a visual reference to the period of the Knights. Characteristic examples of this treatment include the Hotel Thermae and the Palazzo Littorio, which later became the City Hall.

Rodi's "Cattedrale Cattolica San Giovanni " in 1939

Rodi's "Cattedrale Cattolica San Giovanni " in 1939

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment